The Alta Collection

[SHAKESPEARE, William?]

Manuscript fragment of Vincent of Lérins’ Commonitorium

$25000

Item Details

A previously unknown manuscript written in Elizabethan handwriting with paleographic features linking it closely to Shakespeare’s.

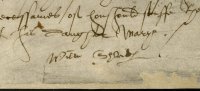

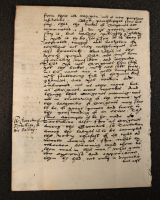

[SHAKESPERE, William?]. A single leaf from Vincent of Lérins’ Commonitorium on laid paper, 127 x 178 mm. Written in secretary hand in a single column, unruled, on recto (37 lines) and verso (34 lines).

Few handwriting quirks are as universally known as William Shakespeare’s famous “spurred a.” Indeed, in reviewing a recent exhibition at the British Library, Jennifer Young relates the thrill of finding herself “standing just a thin pane of glass away from the spurred ‘a’ of the playwright’s own hand in the Sir Thomas More manuscript.”

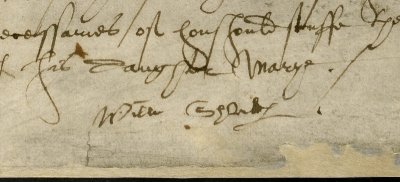

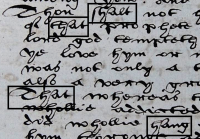

This unique feature of William Shakespeare's handwriting is the way that he connects the cursive letter h with a following a, in which the low loop of the h leaps into a high arch that transitions into the a, a feature found only in his signature "Shakespeare" on a legal document (the Bellott–Mountjoy case of 11 May 1612, see illustration) and in the three pages of his manuscript play Sir Thomas More.

In 1916, Edward Maude Thompson, the first director of the British Museum, reported that he had not observed this arched “h-a” construction elsewhere “in the numerous documents of the period that have passed under my eyes.” In 1961, C. J. Sisson recounted that “during some forty years of continuous reading of contemporary manuscripts, amounting perhaps to half a million sheets,” he had discovered no instances of the peculiar form of “h-a” other than in Shakespeare’s signature and Sir Thomas More. In 1990, Giles E. Dawson examined a sizeable collection of letters and documents written by 250 Elizabethan and Jacobean authors and offered further corroboration that the arched “h-a” ligature appeared to be unique to Shakespeare. In 2011, John Jowett’s Arden Shakespeare edition of Sir Thomas More noted the absence of the “form of joined h-a” in “the handwriting of any other writer.” MacDonald P. Jackson postulated that the odds of finding the construction in another manuscript “must be astronomical.”

The unique Shakespearean "h-a" form, however, has now been discovered in another Tudor manuscript: a small leaf of laid paper, measuring about 5 x 7 inches, both sides of which contain a neat block of text in Elizabethan secretarial hand, surrounded by wide margins. The text itself is a previously unknown English translation of a passage of the 5th-century Commonitorium written by a monk named Vincent who lived at Lérins Abbey on the island of Saint-Honorat (near present-day Cannes, France).

Vincent of Lérins’ Commonitorium was published in many editions during the early Renaissance, but possession of this Catholic text was “unlawful” in Protestant Elizabethan England, so this manuscript may well have been hidden in Shakespeare’s time and remained so for centuries.

News of the discovery was announced in The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 2024. Leading paleographers and Shakespearean scholars worldwide agree that there is a pronounced similarity between the “h-a” ligatures in the Vincent manuscript and those written by Shakespeare. (See photos for comparison of the words "that," "what," and "hands" in Sir Thomas More and "that," "hang," and "shalt" in the Vincent manuscript. Many words such as "certayne" and "error," also illustrated with the Sir Thomas More exemplar on the left and the Vincent manuscript exemplars on the right, are extremely similar in the two hands.)

There are, of course, two ways to interpret the evidence of this discovery. On the one hand, it may be that the arched “h-a” form is not unique to Shakespeare after all and that the Vincent manuscript is the rule-proving exception.

On the other hand, if we maintain that the “h-a” form is unique to Shakespeare, then we are faced with the provocative possibility that this handwritten manuscript is Shakespeare’s. As such, it possesses an almost mystical allure that seems to invite us back in time to the moment of creation. One might imagine that perhaps early in his career, before he established himself as a professional playwright, Shakespeare did odd jobs working as a scribe, and this fragmentary leaf, with its transcription of an obscure theological text, is the only extant example of his work.

Literature:

Jennifer Young, Shakespeare in Ten Acts and Discovering Literature: Shakespeare Review | Reviews in History, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/1983.

E. Maude Thompson, “The Handwriting of the Three Pages Attributed to Shakespeare Compared with his Signatures,” in Shakespeare’s Hand in the Play of “Sir Thomas More,’” ed. A. W. Pollard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923), pp. 57-112.

C. J. Sisson, “Postscript” to R. A. Hubler, “On Looking over Shakespeare’s ‘Secretarie’,” in Stratford Papers on Shakespeare, ed. B. A. W. Jackson (Toronto: W. J. Gage, 1961), pp. 70–77.

Giles E. Dawson, “Shakespeare’s Handwriting,” Shakespeare Survey 42 (1990): 119-28.

MacDonald P. Jackson, "Is “Hand D” of Sir Thomas More Shakespeare’s? Thomas Bayes and the Elliott–Valenza Authorship Tests." Early Modern Literary Studies 12.3 (January, 2007) 1.1-36 <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/12-3/jackbaye.htm>.

John Jowett, ed. The Book of Sir Thomas More, The Arden Shakespeare Third Edition (London: Methuen, 2011), pp. 440-1.

Eric Rasmussen and Molly G. Yarn, “A Newly Discovered Manuscript of Vincent of Lerins’ Commonitorium and Shakespeare’s Hand D in Sir Thomas More,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 113 (2024): 451-61.

__________________________

Transcription by Karen Norwood

Recto

1. very same man Origenes , not with

2. standing he was so singuler and

3. so excellent a man , and such a one

4. as before is declared yet whiles

5. that he insolently abuseth the grace

6. of god , whiles that he foloweth too

7. much hys owne witt , and trusteth

8. too much to his owne judgement the

9. whiles that he litle regardeth the

10. old ancient simplicitie of Christian

11. religion , whiles that he presumeth

12. to be wiser , then all others whiles

13. that he confermeth the ecclesiasticall

14. traditions , and the rules & teachings

15. of the elders , and expoundeth

16. certayne places of scripture

17. after a new fashion : He wer:

18. -thilie deserved , that of hym also

19. it shold be saide unto the church

20. of god. If a prophete arise

21. among you . and a little after .

22. Thou shalt not heare the wordes

23. of that prophete . for that your

24. lord god tempteth you , whether

25. ye love hym or not. Truly it

26. was not only a temptation , but

27. also a very great temptation ,

28. That whereas the church was

29. whollie addicted to hym , and

30. did whollie hang and stay uppon

31. hym thorough admiration of his

32. witte , knowledge eloquence ,

33. conversation and grace and nei:

34. -ther feared nor suspected any

35. evill of hym , soddenly by a litle

36. and a litle to leade them a side

37. from their

Verso

1. from their old religion into a more prophane

2. infidelitie . But perhappes some will

3. say , that the books of Origenes are

4. corrupted . I do not greatly gaine

5. say it , but rather willingly & gladly

6. I yeld it to be soe proper it is even so

7. reported , taught and wrytten of

8. certayne not only catholicques , but

9. also heretics . But : this is the

10. wery point that we must note?

11. specially confident , and regarde

12. That yf not Origenes hym self

13. yet the bookes which are sett forth

14. in his name are a great temptation

15. which scattering full of heynous Blas:

16. -phemies , are yet readen and

17. embraced , not as other mens , but

18. as Origenes ownen worckes , and

19. though that Origenes meaning was

20. not in conceaving of the error : yet

21. the authoritie of Origenes may seme

22. to be of great power and force to

23. the pervading of an error . The

24. same accounte is to be made of

25. Tertullian also ... for as Origenes

26. [The Character of] among the Grecians , so Tertullian

27. [Tertullian, & ] among the Latyns is to be accounted

28. [His Failing.] the very chiefest of all , that ever

29. wrote among us ffor what ex:

30. -cellenter learning could there be

31. then was in this man ? What grea:

32. -ter exercise and experience

33. then he had , not only in divinite

34. but also ‘

The Alta Collection

Eric Rasmussen

1004 Placid Creek Ct

Round Rock, TX, 78665

United States

Phone: 9252124132

Featured Catalogue

Visit Website

Specialities

Shakespeare, Early English Books, Manuscripts

More Information

Booth 5

Shipping and Returns

2-day FedEx, USPS, or UPS shipping