Alexandru Matveev

Letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Emperor Nicholas II. Vols. I–II. Berlin, 1922; Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov. Vols. III–V. Moscow–Leningrad, 1923–1927.

$1900

Item Details

Berlin, 1922, Paperback

First edition, Good

Letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Emperor Nicholas II. Vols. I–II. Berlin, 1922; Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov. Vols. III–V. Moscow–Leningrad, 1923–1927.

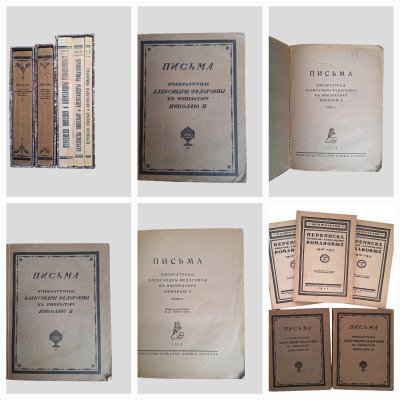

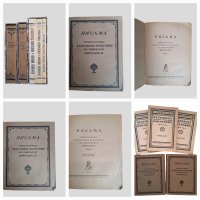

Letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Emperor Nicholas II. Translated from English by V.D. Nabokov. Volumes I-II. Berlin: Slovo, 1922.

Volume I: [4], 642, [2] pages

Volume II: [2], 496, [2] pages

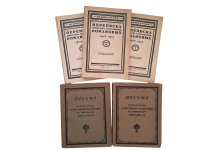

Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov. With a preface by M.N. Pokrovsky. Volumes III-V. Moscow-Leningrad: State Publishing House, 1923–1927. Volumes I and II did not appear. Published under the designation “Central Archive.”

Volume III: Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov, 1914–1915. Moscow–Petrograd, 1923. XXXIV, [2], 512, [10] pages; 3 facsimile leaves. Print run: 10,000 copies.

Volume IV: Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov, 1916. Moscow–Leningrad, 1926. XVI, 438, [2] pages. Print run: 5,000 copies.

Volume V: Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra Romanov, 1916–1917. Moscow–Leningrad, 1927. XIV, [2], 304 pages. Print run: 5,000 copies.

The books were never reissued. In five contemporary half-leather bindings. Original printed dust jackets preserved. The covers of volumes published during the Soviet era were designed by A. Leo. Excellent condition. The editions are of great historical value and rarity.

Bibliography: The Berlin edition is listed in the card catalog of émigré publications collected by Andrey Savin (“Russia Outside Russia” – Andrey Savin Electronic Library).

The history of these two editions is well known and resembles a tightly-wound detective story, where politics, psychology, personal space, and secrecy are closely intertwined.

Both editions contain letters of the imperial couple during World War I, 1914–1917. The Berlin edition includes letters from Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to her husband. They are rich in details about the family life of the emperor, as well as domestic and international political affairs during the war. Central figures in the letters include Lady-in-Waiting A.A. Virubova and Grigory Rasputin, appearing under code names “Anya” and “Our Friend.” The letters reveal the mysterious influence of the peasant “elder” who, according to the former empress, even “controlled the mists on the front,” and they show the inner workings of the “ministerial shuffle” during the final years of Nicholas II’s reign, intrigues against Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, the State Duma, etc. From the correspondence, Rasputin’s real role in behind-the-scenes political struggles is evident, influencing the emperor and the state system through the empress.

Against the backdrop of high politics, army intrigue, and numerous state and domestic issues, the correspondence devotes considerable attention to intimate details of the imperial family’s life. The letters reveal a vivid psychological portrait of the Empress and Nicholas II as real people bearing the heavy responsibility of ruling the Russian Empire.

Personal and political matters are remarkably intertwined in these letters. Alexandra Feodorovna actively involved herself in domestic policy, advising her husband on appointments and decisions, providing her own assessments of the state situation. She often noted that “letters may be read by outsiders,” so she used hints, code words, nicknames understandable only to Nicholas II. The letters can be read in different ways. They are full of the empress’s love for her husband and demonstrate the incredible trust the emperor placed in her, consulting her on all matters and relying on her intuition.

The letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna during World War I were immediately recognized by various political forces as highly significant. That is why her letters were first sent abroad and published as the most relevant part of the Imperial personal archive. The archive as a whole was invaluable, containing answers to most domestic and international policy questions over 20–30 years. Under different, more favorable circumstances, the archive could only have been declassified and published decades later.

The history of the Imperial archive is remarkable. After the family’s execution, their letters and documents were transferred from the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg into state custody. Not long before the execution, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) declared all the Imperial family’s property—including personal archives—as state property. The Soviet historians immediately recognized the value of the Romanov archive. A team of journalists, scholars, and archivists worked on reviewing and preparing the documents for publication, led by professors M.N. Pokrovsky, V.N. Storozhev, A.A. Sergeev, L.S. Sosnovsky (editor of Pravda), and historian V.V. Adoratsky.

All personal documents of the imperial couple were crucial for the Bolsheviks. Alexandra’s letters clearly showed that the monarchy had contributed to its own downfall, being manipulated and guided by irrational motives. The Bolsheviks’ arrival from Germany in a sealed train was not the cause. Justifying the October Revolution was a primary goal of M.N. Pokrovsky, who oversaw the review and publication of Nicholas II’s and Alexandra’s personal materials.

Pokrovsky began studying the imperial papers in July–August 1918, immediately after they came into Soviet hands. He considered Alexandra’s wartime letters far more interesting than Nicholas II’s diaries. From August 9, 1918, fragments of the personal archive were selectively published in Pravda and Izvestia, focusing first on 1905 and 1917 materials, then on diaries and letters from the Russo-Japanese War and World War I.

The publications also served to “expose the imperial family” and monarchists. The Berlin edition of Letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna by the Slovo Publishing House, apparently created for the Cadet Party’s interests, aimed to achieve the same purpose: to absolve the Cadets and the Provisional Government of responsibility for the revolution.

In 1919, Professor V.N. Storozhev, a close associate of Pokrovsky, undertook copying and preparing the documents. Documents held in the Central State Archive were highly confidential. Storozhev, as manager of the Novonikolaevsky Archive, had unrestricted access, and in 1919–1920, up to five copies were made of each document (instead of the required two). Copies were sometimes hurried and contained small differences from the originals, such as punctuation and abbreviations.

By 1921, Storozhev secretly sent copies of several key document groups, including Alexandra’s letters from 1914–1917, to Berlin. Slovo Publishing House acquired the rights to publish and translate them.

By November 1921, Soviet archivists investigated why excerpts of secret archival files were being published abroad. Storozhev was dismissed, and his home copies confiscated. The Berlin publications in 1922–1923 triggered an internal investigation into how the documents reached Germany.

The Soviet publication of Nicholas II’s and the imperial family’s materials was later associated with the eminent Russian archivist Alexander Alexandrovich Sergeev (1886–1935). He also investigated how copies ended up in Berlin, concluding: “This is undoubtedly theft; the materials could not have reached Slovo legally.”

The Berlin edition included Russian translations by Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (1869–1922), a Cadet Party leader, criminal law professor, and journalist, father of the writer Vladimir Nabokov. Letters were also published in the original English. Volume II contains an index. The letters cover April 27, 1914 – December 17, 1916, not including the February Revolution or Nicholas II’s abdication.

Soon after the publication, Russian historian and Cadet A. Kizevetter reviewed the letters in Sovremennye Zapiski (1922, vol. XIII), stating:

“The published letters are of primary historical importance. They shed light on Alexandra Feodorovna’s role in the unconscious preparation for the monarchy’s collapse... Alexandra was the inspirer of an ultra-reactionary course that isolated the monarchy from the living forces of the country.”

Both émigré publishers and Soviet historians critically assessed the letter’s authors. Kizevetter described the empress as ambitious, impassioned, and prone to delusions and irrational thought. Pokrovsky’s criticism was even harsher.

A.A. Sergeev also reviewed the Berlin edition, criticizing the low scholarly and technical level, the rushed editing, and translation errors. Occasionally, 15–20 lines were missing from the English originals. Another key factor in the criticism was competition between the two editions.

The Central Archive began the scholarly publication of the Romanov documents in 1923. Sergeev’s Soviet edition, Correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra, Vols. III-V (State Publishing House, 1923–1926), was the first to publish documents systematically and methodically. It strictly adhered to the originals, including letters and telegrams in Russian translations. Sergeev identified all persons referred to in shortened or coded forms.

Sergeev, a young scholar of the old school, was politically neutral and meticulous. Some prepared materials were never published due to the political climate in the late 1920s and his early death. For instance, Nicholas II’s diaries for 1882–1918 remain unpublished, and their location is unknown.

While the Berlin edition was intended for a broad readership among Russian émigrés and English-speaking Europeans, the Soviet edition was aimed at professional researchers. Sergeev’s work ensured that names and details were correctly identified and translated.

Both editions of Alexandra Feodorovna and Nicholas II’s correspondence are of immense importance for Russian history. Their preparation and analysis contributed significantly to the study of Russian history. The Berlin edition complements the Soviet edition by including the English originals of the empress’s letters. Both are extremely rare.

Alexandru Matveev

Alexandru Matveev

80/3a sudecka

Wroclaw, Lower Silesia, 53-129

Poland

Phone: +48726443990

Featured Catalogue

Specialities

Eastern Europe, Poland, Rossica, Russia

More Information

Booth 4

Shipping and Returns

Estimated delivery time from 2 to 4 weeks to USA and 5 working days to Europe. Expedited shipping.30 day return guarantee, with full refund including original shipping costs for up to 30 days after delivery if an item arrives misdescribed or damaged.

Payment options: Bank transfer, PayPal.

Additional Information

I'm an independent bookseller/collector focusing mainly on Eastern European and Russian antiquarian books, with over 15 years of experience.